Distrusting democrats: A panel study into the effects of structurally low and declining political trust on citizens’ support for democratic reform

Abstract

For decades, scholars have argued that low and declining political trust affect citizens’ support for democratic and undemocratic reform. While some theorized that low political trust induces alienation and support for non-democratic decision making, others argued that it pushes critical citizens to support reforms aimed to reinvigorate democracy. Yet, empirical tests of these expectations remained sparse and inconclusive. This paper employs panel data from the Netherlands (covering 3 waves in 3 years) to test these diverging theories simultaneously. We employ the random effects within-between (REWB) model to differentiate between the effects of structurally low and declining political trust. Our results suggest that low and declining trust both diminish support for representative democracy, enhance support for direct democratic decision making and do not affect support for authoritarianism. These findings cast doubt on the understanding of political distrust as a determinant of political alienation. Rather, they support theories of critical citizenship and stealth democracy.

Introduction

‘Interest in political trust rests largely on beliefs about its consequences for the effectiveness of government and democratic stability’ (Citrin & Stoker, 2018, p. 61). Indeed, students of political trust have long sought to identify its consequences (e.g., Crozier et al., 1975; Finifter, 1970). Some scholars warn that low political trust turns people away from democracy (Miller, 1974), whereas others take a more hopeful stance, arguing that low trust is essential to reinvigorate democratic systems (Rosanvallon, 2008). The debate rests, in part, on the belief that political trust affects the institutional configuration of representative democracy (cf. Kaase & Newton, 1995), particularly because low and declining levels of trust influence citizens’ attachment to democratic decision-making arrangements. Yet, empirically, these hypothesized effects of political trust remain rather unclear.

Existing scholarship proposes seemingly opposite claims about the effects of low political trust on support for democratic reforms, ranging from a hopeful revitalization of democracy (Dalton, 2004; Norris, 1999b) to a detrimental tendency to support technocracy and authoritarian-rule (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002; Mounk, 2018). Three sets of theories stand out for their longevity: alienated, critical, and stealth democratic citizenship. Theories of alienation posit that low levels of trust yield a withdrawal from politics (Citrin et al., 1975; Crozier et al., 1975, p. 159; Finifter, 1970; Krastev, 2016; Mair, 2013). Critical citizenship suggests that low trust motivates citizens to seek more democratic control over decision-making processes and elected representatives (Dalton et al., 2001; Norris, 1999b, 2011). Finally, stealth democracy tentatively relates low trust to support for both direct, technocratic and authoritarian modes of democracy (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002). The empirical literature predominantly developed these theories in isolation, focusing on effects rather than on the mechanisms that might allow us to distinguish between the three theories that we claim are not mutually exclusive.

Moreover, rigorous tests remain sparse. Empirical evidence rests primarily on cross-sectional analyses. While useful, these cross-sectional designs conflate levels of political trust with its dynamics (Levi & Stoker, 2000, p. 489). That conflation hinders the simultaneous test of the three rivalling but potentially complementary theories. Indeed, estimated effects are rather inconclusive. Some suggest that low trust and dissatisfaction yields support for specific decision-making reforms, though even the direction of these effects themselves are contested (Bowler et al., 2007; Coffé & Michels, 2014; Dalton, 2004; Dalton et al., 2001; Norris, 1999b; Schuck & de Vreese, 2015; Werner, 2020), while others cast doubt on this view (Donovan & Karp, 2006; Gherghina & Geissel, 2019, 226).

In this article, we start from the assumption that there need not be a singular response to low political trust. Rather, we argue, the three overarching theories provide differential expectations about the effects of low political trust on support for decision-making reforms. To disentangle the three dominant theories, it is crucial to separate the effects of structurally low from dynamically declining political trust. This disentanglement allows us to overcome theoretical and empirical limitations in the literature. First, we identify rivalling mechanisms and outcomes proposed by the longstanding theories of alienated, critical and stealth democratic citizenship, arguing they play out at different levels of analysis and at different outcomes. Second, we propose a research design that provides a more crucial test of these theories, by separating structurally low from dynamically declining political trust and support for decision-making reforms. To that purpose we employ 3-year longitudinal panel data in combination with a hierarchical within-between model (Bell & Jones, 2015).

Our findings underpin the relevance of the theoretical and methodological innovations of differentiating between low and declining levels of political trust to test key mechanisms and outcomes proposed by the three rivalling theories. First, low and declining political trust are associated with a rejection of representative decision-making processes. Second, we find no evidence whatsoever for the alienated citizenship theory, partial support for stealth democracy theory, and primarily support for critical citizenship theory. Third, our findings illustrate the need to disentangle structurally low trust from declining trust: the two components have distinct effects on preferences for decision-making arrangements.

Theory: Political trust, alienated citizens, critical citizens and stealth democrats

Research on decision-making reforms typically envision political trust attitudes as part of broader ‘dissatisfaction hypothesis’ (Dalton, 2004). Its absence is a catalyst for change that generates a shift away from the status quo (Miller, 1974, p. 951).

Political trust is best understood as a form of political support with three distinct features. First, political trust is ‘a middle-range indicator of support’ oriented towards institutions (Zmerli et al., 2007, p. 41). As such, it consist of both a diffuse and specific component (Craig et al., 1990; Easton, 1975; Hetherington, 1998, p. 792; Weatherford, 1987) and stands ‘between the specific political actors in charge of every institution and the overarching principles of democracy in which specific institutions are embedded in a given polity’ (Zmerli et al., 2007, p. 41).1 Second, political trust is relational: trust is relational, reflecting an attitude in which a subject (A) trusts an object (B) in a given domain of action (X) (Hardin, 2002). Third, trust is inherently tied to vulnerability, risk and uncertainty. To trust is to accept ‘vulnerability; there is always a risk of betrayal or failure’ (Citrin & Stoker, 2018, p. 50). In sum, ‘political trust can be understood as … support for political institutions such as government and parliament in the face of uncertainty about or vulnerability to the actions of these institutions’ (Van der Meer, 2017, p. 1).

Trust in representative institutions enables citizens to delegate decision making to a set of actors and institutions, while making themselves vulnerable to these actors in the face of uncertainty. This logic drives the oft-proposed link between low political trust and preferences for decision-making reforms. Lacking trust in representative institutions, citizens may be reluctant to delegate decision making to elected representatives and instead demand change in decision-making processes. This expectation features in various empirical studies aiming to explain support for specific decision-making arrangements (Bengtsson & Mattila, 2009, p. 1032) such as referenda (Bowler et al., 2007; Donovan & Karp, 2006; Mohrenberg et al., 2021; Schuck & de Vreese, 2015; Werner, 2020), sortition (Bedock & Pilet, 2020), electoral reforms (Dalton, 2004; Dalton et al., 2001) or technocracy (Bertsou & Pastorella, 2017).2

Yet, although trust can be understood as an indicator of support facilitating delegation, the consequences of its absence are far from obvious. Theoretically, the conceptualization of low political trust as a straightforward anti-status quo attitude is more complicated. Some theories suggest low political trust drives citizens to reject democratic procedures, others view it as a force for democratic reinvigoration. Three main sets of theories were developed over the years: theories of Alienation since the 1960s and 70s, and theories of critical citizenship and stealth democracy since the 1990s.

Scholarship from the 1960s and 70s suggested that longstanding and generalized distrust of government institutions leads to alienation, ‘a relatively enduring sense of estrangement from existing political institutions, values and leaders’ (Citrin et al., 1975, p. 3). In the very same year, Crozier et al. (1975, p. 159) argued: ‘The lack of confidence in democratic institutions is clearly exceeded by the lack of enthusiasm for any alternative set of institutions’. Such alienation, scholars argued, poses a threat to representative democracies because alienated citizens may fail to support their governments in times of crisis (see also King, 1975). Political alienation leads citizens to reject existing decision-making structures. The rejection may either take the form of complete withdrawal from politics (e.g., Crozier et al., 1975) or as Miller (1974, p. 951) argues ‘revolutionary alteration of the political and social system’ (Finifter, 1970).3 The influence of these alienation theories is felt throughout the political trust literature (Van der Meer & Zmerli, 2017), and has been revisited in recent scholarship on democratic deconsolidation (Krastev, 2016; Mair, 2013; Mounk, 2018).

Nevertheless, two rivalling theories were developed. For proponents of critical citizenship, low trust does not induce alienation, but reflects engaged criticism. This theory emphasizes the adaptive nature of democratic institutions (Kaase & Newton, 1995). Low levels of trust are central to this process of adaptation. Norris (1999b, p. 21) argues that low trust in representative institutions makes democracy stronger by fostering a desire for change. Critical citizens do not reject democracy or fail to defend it when needed. Instead, critical citizens have ‘high democratic aspirations’ (Werner, 2020). Distrust of representative institutions motivates them to demand more democracy, more citizen-influence over decision-making processes, and more control and accountability of elected officials (Cain et al., 2003; Dalton, 2004). In line with this hypothesis, various studies find a correlation between low political trust and dissatisfaction on the one hand and support for decision-making arrangements that enable greater citizen input on the other. Among these arrangements are referenda (Coffé & Michels, 2014; Dalton et al., 2001; Schuck & de Vreese, 2015), general modes of direct democracy (Gherghina & Geissel, 2019) and sortition models (Bedock & Pilet, 2020). In this perspective, critical citizens help close the gap between democratic ideals and the current functioning of government.

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2002) tone down this optimism. Distrusting citizens, they argue, can also be Stealth Democrats. Stealth democrats are apolitical. They do not inherently want to be bothered with the daily grind of decision making and prefer effective and efficient decision making over the conflict and compromise required in every-day politics (cf. Ackermann et al., 2019; König et al., 2022). Yet, the democratic nature of stealth democrats has been pushed to the background. Stealth democrats adopt an emergency-brake approach to accountability. While they are happy to leave daily affairs to apolitical experts, they also want the option to step-in the decision-making process when they find it necessary to do so (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002, pp. 2, 131).4

While critical citizens welcome direct forms of decision making, stealth democrats reluctantly gravitate toward these options out of distrust (cf. Mohrenberg et al., 2021; Stoker & Hay, 2017). Stealth democrats may strive for decisive direct democratic institutions that allow them to step in to correct leaders when need be (as an emergency brake) and simultaneously gravitate toward decision-making arrangements that vest power in competent effective leaders such as technocrats and business leaders. Stealth democracy theory thus proposes a more fragile link between low political trust and support for democratic reforms. For stealth democrats, low trust does not uniformly yield a push for more democracy, but rather a rejection of the status quo that stimulates direct democracy (on key issues) as well as depoliticized decision making (on day-to-day affairs).

Hypotheses: Low versus declining political trust

All three theories envision that low political trust generates a rejection of the status quo. However, they differ as to whether this rejection constitutes a relatively indiscriminate step away from democratic politics, a step toward specific types of reform or a mixture of both. To better understand the theorized effects of low trust on citizens’ support for decision-making reforms, we assess these rivalling theories simultaneously. We do so by comparing (i) the types of decision-making reforms each theory predicts and by (ii) differentiating structurally low political trust from declining political trust.

We propose a theoretical and empirical distinction between the level of political trust and its dynamics, that is, between low and declining trust. Hypotheses about the consequences of trust often rely on descriptions of macro- or micro-dynamics such as decline (Christensen, 2018, p. 577; Dalton, 1999; Hetherington, 1998, p. 799; Lipset & Schneider, 1983), growth and increase (Bengtsson & Mattila, 2009, p. 1033; Dalton, Burklin, & Drummond, 2001, p. 148; Miller, 1974, p. 971) and durability (Miller, 1974, p. 951).

Studies that model these dynamics primarily do so at the macro-level, employing countries and regions as the primary unit of analysis and/or focus on policy reforms (Chanley et al., 2000). Yet, macro-level studies do not shed much light on the consequences of low trust that we expect to take place at the individual-level. Meanwhile, individual-level studies on the consequences of trust, overwhelmingly rely on cross-sectional designs that cannot account for these dynamics. They can only differentiate between individuals with low versus high trust, and as a result conflate differences between individuals with within-person changes. The diagnosis of Levi and Stoker (2000, p. 489) continues to ring true: hypotheses relying on the dynamics of trust attitudes have ‘not been evaluated by survey researchers (since it requires long-term panel data)’.

Nevertheless, theories of Alienated, Critical and Stealth Democratic Citizenship raise different expectations about static low trust and dynamically declining trust. Political (dis)trust does not need to have a singular effect. Rather, the mechanisms proposed by the three theories can therefore be complementary (cf. Bengtsson & Mattila, 2009, p. 1045; Webb, 2013, pp. 767–768). While all three theories assume that distrust erodes support for the status quo, they differ in the way that this effect plays out at different levels and in favour of different rivalling models of democracy.

Static effects

- H1: The lower the structural level of political trust (between-person), the lower the support for representative decision-making models (the status quo).

- H2: The lower the structural level of political trust (between-person), the higher the support for authoritarian decision-making.

- H3a: The lower the structural level of political trust (between-person), the lower the support for direct democracy.

- H3b: The lower the structural level of political trust (between-person), the higher the support for direct democracy.

Dynamic effects

In contrast to alienated citizens and stealth democrats, the theory on Critical Citizens places less emphasis on low trust as a stable unchanging disposition. Critical citizens are by definition evaluative (Norris, 1999b). Their attitudes toward government institutions and officials are responsive to the government's policy and process performance (Miller & Listhaug, 1999). Their ‘evaluations about the performance of the government are predicted to fluctuate over time, but [their] generalized attachments to the nation-state are expected to prove more stable and enduring, providing officeholders with the authority to act based on a long-term reservoir of favourable attitudes or affective goodwill’ (Norris, 2011, p. 22).

- H4: The more a person's political trust declines (within-person), the lower their support for representative decision-making models (the status quo)

- H5: The more a person's political trust declines (within-person), the lower their support for authoritarian decision making.

- H6: The more a person's political trust declines (within-person), the higher their support for direct democracy.

Table 1 provides a schematic overview of these expectations.

| Political trust | Representative decision-making | Authoritarian decision-making | Direct democratic decision-making |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structurally low trust |

↓ Alienated (H1) ↓ Stealth (H1) |

↑ Alienated (H2) ↑ Stealth (H2) |

↓ Alienated (H3a) ↑ Stealth (H3b) |

| Declining trust | ↓ Critical (H4) | ↓ Critical (H5) | ↑ Critical (H6) |

Data and methods

Data

A decisive test of these hypotheses places some demands on the data we employ. First, we need individual-level data. While scholars have long relied on aggregate trends to study the effect of political trust at the macro-level, theories of Alienated, Critical and Stealth Democratic Citizenship are ultimately micro-level theories. Second, we need longitudinal panel data over a relatively long timespan that allows us to separate structurally low from dynamically declining trust. This requires repeated measures of citizens’ political trust, as well as their support for decision-making reforms.

To meet these requirements we rely on a three-wave panel dataset collected between 2017 and 2020 in the Netherlands. This data set is an extension of the Dutch Parliamentary Election Survey of 2017 (see www.dpes.nl), followed by two additional waves designed specifically for this paper. The 3-year period over which the surveys were administered enables us to assess long-term developments in citizens’ trust attitudes, while avoiding tapping into partisan-driven trust resulting from interfering national elections (which did not take place until 2021).

Respondents were drawn from a nationally representative probability household sample (itself drawn by Statistics Netherlands) from the academic Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS). All three surveys were administered online. In total 1,180 respondents participated in Wave 1 (i.e., DPES 2017) between 16th and 28th March, 2017. A total of 1,061 of them were contacted and 856 (80.7%) completed a follow-up survey (Wave 2) between 6th and 21st May, 2019. The final survey wave (Wave 3) took place between 1st and 29th June, 2020, a period marked by increased levels of political trust due to rally-effects from the Covid-19 pandemic (Schraff, 2021).5 Out of 1,250 respondents that were approached (all respondents from Wave 2, added with respondents who only participated in Wave 1), 1,081 (86.5%) responded to the survey.6

Operationalization

Dependent variables

We measure support for decision-making reforms with five distinct survey items with five-point Likert scales (ranging from Strongly/Fully disagree to Strongly/Fully agree).7 These five items tap into respondents’ preferences for delegation (the status quo of representative democracy), authoritarian-rule and direct democracy (citizen-elected Prime Minister; referendum). Support for delegation was measured via the survey item: ‘I am in favor of a democracy in which: Citizens choose the parliament, and the parliament subsequently makes the decisions’. We measure support for authoritarian rule via the item ‘Having a strong leader in government is good for the Netherlands even if the leader bends the rules to get things done’. The latter item measures political authoritarianism, though not necessarily undemocratic authoritarianism. Lastly, debates on direct democracy in the Netherlands are dominated by two elements, direct election of the (in the Netherlands unelected) Prime Minister and the use of referenda. Support for the direct election of the Prime Minister is measured via the item: ‘The Prime Minister should be directly elected by the voters’. To measure support for referenda, respondents were asked to rate two items (1) ‘I am in favor of a democracy in which as many decisions as possible are made based on referendums’ and (2) ‘On some of the important decisions that are to be made in our country voters should be able to vote by means of a referendum’. Together, these items tap into respondents’ support for direct democratic reforms. See Appendix Table A1 for the mean and standard deviations of each of these variables across each survey-wave.

Independent variables

We measure political trust via a standard battery that asks respondents to indicate how much trust they have in three institutions – parliament, government and political parties – on a 4-point scale ranging from (1) Very Much to (4) No trust at all.8 The reverse coded trust items entail that lower values reflect a lot of trust while higher values reflect no trust at all. The three items are conventionally used in political trust research. Because they form a strong hierarchical scale (Chronbach's Alpha ranges from 0.86 in 2020 to 0.87 in 2017; Loevinger's H ranges from 0.81 in 2017 to 0.84 in 2020) we combined the items into an average score. Appendix Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of each item across waves.

We effectively operationalized structurally low political trust as a respondent's average distrust in these three institutions over the 3-year period. Dynamically declining political trust is operationalized as the downward shift in trust in these three institutions between subsequent waves. This differentiation provides a strategy to empirically isolate the stable diffuse component of trust from its rather fluctuating specific component (cf Easton, 1975), and thereby test expectations put forward in theories of Alienated, Critical and Stealth Democratic Citizenship.

Control variables

In line with existing literature, we adjust for various confounding factors that may influence both political trust and support for decision-making reforms. These include political preferences (vote choice in the 2017 Dutch general elections; left-right placement in 2017), political interest and internal efficacy (Bengtsson & Mattila, 2009; Coffé & Michels, 2014). Internal efficacy is operationalized as, (1) the extent to which respondents felt they understood important political issues and (2) believed themselves capable to play an active role in politics. Our models also adjust for demographic characteristics (gender, education levels and age) and household income levels. All control variables were measured in 2017 and modelled as baseline covariates.

Analytical approach

We employ within-between random effects models (Bell & Jones, 2015) to estimate the effects of within-person changes in trust as well as the effects of between-person differences. These REWB models have recently gained in popularity as they combine both fixed and random effects within a single hierarchical model. Applied to panel-data, such models allow for a fixed-effect specification of individual-level changes over time at level 1 while at the same time providing an estimate of differences between-individuals at level 2 (Bell et al., 2019). As a result, we are able to disentangle political trust into two components: (1) the yearly deviation from each individual's average distrust (to assess the effect of declining trust within-individuals), and (2) each individual's average level of distrust over the three-year period (to assess the effect of structurally low levels of trust). Although the approach does not mitigate endogeneity risks resulting from reverse causation, the fixed effects model (level-1) improves on existing studies by minimizing endogeneity risks due to confounding by time invariant characteristics.9 At level-2, we adjust for a number of time-invariant factors listed in the previous section. Finally, additional analyses tested for the risk of bottom- and ceiling-effects by truncating the data (removing the 5% most and 5% least trusting respondents from the sample). We found our findings were highly robust (see Appendix Table A5).

Results

Our null models include a time-adjustment for the sample as well as between-person varying intercepts in decision-making preferences (see Table 2). As indicated by the ICC, between-person differences explain most of the variation in support for frequent and selective referenda; accounting for approximately 70 per cent of the total variance. Support for direct election of the PM also varies mostly between individuals (ICC ∼ 0.60). This proportion is lower for support of delegation and authoritarian-rule for which 43 and 48 per cent of the total variance, respectively, occur between individuals. These patterns suggests that preferences for direct decision-making arrangements are relatively more stable over time than preferences for delegation and authoritarian-rule (cf. Werner, 2020).10

| M1: Delegate | M2: Strong leader | M3: Referenda | M4: Referenda important | M5: Elect PM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | Se |

| (Intercept) | 3.96 *** | 0.03 | 3.12 *** | 0.03 | 2.58 *** | 0.03 | 3.35 *** | 0.04 | 3.14 *** | 0.04 |

| 2019 | −0.17 *** | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 *** | 0.03 | −0.20 *** | 0.03 | −0.08 * | 0.04 |

| 2020 | −0.17 *** | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.15 *** | 0.03 | −0.21 *** | 0.03 | −0.14 *** | 0.03 |

| Random Effects | ||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.54 | |||||

| τ00 | 0.30 id | 0.52 id | 0.85 id | 1.03 id | 0.81 id | |||||

| ICC | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.60 | |||||

| N | 1177 id | 1155 id | 1177 id | 1160 id | 1158 id | |||||

| Observations | 2932 | 2888 | 2932 | 2940 | 2898 | |||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.009 / 0.436 | 0.001 / 0.480 | 0.004 / 0.703 | 0.006 / 0.685 | 0.003 / 0.599 | |||||

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

- *** p < 0.001

Compared to 2017, support for delegation, direct election of the prime minister and for the use of referenda on some important decisions declined in 2019 and 2020. Concurrently, support for the use of as many referenda as possible increased in 2019 and 2020 while support for authoritarian-rule (a strong-leader who bends the law to get things done) did not vary significantly with time.

Table 3 includes the two components of political trust – that is, structurally low political trust (between-persons) and declining political trust (within-persons) – as well as various control variables that account for between-person variance.11 The results suggest that political trust attitudes are particularly relevant for understanding why some individuals support certain decision-making arrangements more than others.

| M1: Delegate | M2: Strong leader | M3: Referenda | M4: Referenda important | M5: Elect PM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | Se |

| (Intercept) | 4.26 *** | 0.31 | 2.96 *** | 0.41 | 3.29 *** | 0.40 | 3.22 *** | 0.46 | 3.72 *** | 0.44 |

| Wave (ref: 2017) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | −0.20 *** | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.16 *** | 0.03 | −0.16 *** | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| 2020 | −0.21 *** | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.20 *** | 0.03 | −0.14 *** | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Low Political Trust | ||||||||||

| Within-resp | −0.03 * | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.06 ** | 0.02 |

| Between-resp | −0.13 *** | 0.01 | −0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.25 *** | 0.02 | 0.28 *** | 0.02 | 0.25 *** | 0.02 |

| Left-right position | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.09 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 *** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 * | 0.01 |

| Household income (log) | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.04 | -0.24 *** | 0.04 | −0.16 ** | 0.05 | −0.20 *** | 0.05 |

| Gender: Female | −0.17 *** | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Age (ref: 18–24) | ||||||||||

| 25-34 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| 35-44 | −0.26 | 0.14 | 0.36 * | 0.18 | −0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| 45-54 | −0.00 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.17 | −0.11 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.19 | −0.06 | 0.18 |

| 55-64 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.17 | −0.18 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.19 | −0.14 | 0.18 |

| 65+ | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.40 * | 0.16 | −0.22 | 0.16 | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.21 | 0.18 |

| Education (ref: low) | ||||||||||

| middle | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| higher | 0.22 *** | 0.05 | −0.19 ** | 0.07 | −0.25 *** | 0.07 | −0.16 * | 0.08 | −0.30 *** | 0.07 |

| other | −0.15 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.28 | −0.31 | 0.25 | −0.59 | 0.31 | −0.14 | 0.29 |

| Random Effects | ||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.55 | |||||

| τ00 | 0.21 id | 0.42 id | 0.61 id | 0.79 id | 0.58 id | |||||

| ICC | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.52 | |||||

| N | 1025 id | 1018 id | 1025 id | 1016 id | 1012 id | |||||

| Observations | 2503 | 2418 | 2503 | 2453 | 2413 | |||||

| Marginal/ Cond. R2 | 0.126 / 0.436 | 0.082 / 0.475 | 0.205 / 0.702 | 0.173 / 0.689 | 0.170 / 0.598 | |||||

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

- *** p < 0.001

First, structurally low trust has a strong negative association with delegated decision making (the status quo in representative democracies). This is in line with H1. A unit decrease in trust is related to a 0.13-point decline in support for delegation (see Table 3 Model 1). The full range of effect implies a difference of 1.17 points on a 9-point scale in support for delegation between respondents with the highest and lowest levels of trust in the sample.

Second, structurally low trust has a weak but significant negative association with support for political authoritarianism. This is contrary to H2. Every unit decrease in trust relates to a 0.04-point decrease in support for a strong leader who bends the rules to get things done (see Table 3 Model 2). The full range of the effect suggests that the most distrusting respondents in our sample are 0.36 points less supportive of political authoritarianism than the most trusting respondents. This is quite remarkable in the light of the ongoing claim that low political trust is inductive to authoritarian or even non-democratic modes of governance (cf. Mounk, 2018).

Our results also challenge our expectations specified in H3a, and instead lend support to H3b. Structurally low levels of trust are not negatively associated with support for direct decision making. On the contrary, they enhance it. A unit decrease in trust is associated with higher support of frequent use of referenda (approximately +0.25 points), selective use of referenda (+0.28) and direct election of the Prime Minister (+0.25) (see Table 3 Models 3–5). These effects correspond respectively to a 2.25- and 2.52-point difference in support for direct decision making when comparing the least trusting and most trusting respondents in our sample. Structurally low trust yields higher support for citizen control of decision making. These findings fit the model of stealth democracy better than that of Alienated Citizens.

Next, we focus on the dynamics of trust. Declining political trust has additional effects on preferences for decision-making arrangements, even though these within-person effects of changes appear much weaker than the between-person effects of levels. This suggests that support for various fundamental types of decision-making processes may indeed be more diffuse than the more volatile political trust (cf. Easton, 1975; Norris, 1999b).

Relative to a respondent's 3-year average, a one-point decline in political trust yields a 0.03-point decline in the status quo of delegated (representative) decision making. In other words, rising political trust is related to rising support for representative democracy. This lends support for H4. The negative effects of low political trust on support for representative decision making hold for both structurally low levels of trust as well as declining trust.

Declining political trust has no significant effect on support for authoritarian decision making. Again, these findings challenge our expectations about the role of declining trust and political authoritarianism (H5).

Finally, declining political trust yields support for direct decision making including both frequent and selective use of referenda and direct election of the Dutch prime minister. A one unit-decline in political trust relative to one's three-year average, is related to a 0.04-point increase in support for the frequent use of referenda as well as the use of referenda on important decisions and a 0.06-point increase in support for direct election of the Prime Minister. The pattern largely supports our expectations about the effects of declining trust on support for direct democratic reforms (H6).

Our control variables reveal a number of patterns in support for decision-making reforms. Support for delegation is higher among respondents with higher education, while women tend to be less supportive of this form of decision making. Support for political authoritarianism is higher among those who identify as right-leaning, among women and older respondents, but it is lower among the higher educated. Wealthier and higher educated respondents express less support for both frequent and selective referenda while respondents who identify as right-leaning are much more supportive of the frequent use of referenda. Lastly, similar patterns emerge in support for direct election of the Dutch Prime Minister. Wealthier and higher-educated respondents express less support for this type of decision making in contrast to right-leaning respondents who favour it.

In Table 4, we account for factors that may confound the relationship between political trust and decision-making preferences. These include baseline differences between individuals in vote choice, internal efficacy and political interest.

| M1: Delegate | M2: Strong Leader | M3: Referenda | M4: Referenda Important | M5: Elect PM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se | coef. | se |

| (Intercept) | 4.09 *** | 0.35 | 3.65 *** | 0.47 | 2.64 *** | 0.45 | 2.71 *** | 0.54 | 3.70 *** | 0.50 |

| Wave (ref: 2017) | ||||||||||

| 2019 | −0.20 *** | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.17 *** | 0.03 | −0.16 *** | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| 2020 | −0.21 *** | 0.03 | -0.05 | 0.04 | 0.20 *** | 0.03 | −0.15 *** | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Low Political Trust | ||||||||||

| Within-resp | −0.04 * | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 * | 0.02 | 0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.06 ** | 0.02 |

| Between-resp | −0.12 *** | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.22 *** | 0.02 | 0.25 *** | 0.02 | 0.22 *** | 0.02 |

| Vote choice 2017 (ref: coalition) | ||||||||||

| Left Opposition | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.23 ** | 0.08 | 0.27 *** | 0.08 | 0.33 *** | 0.10 | 0.25 ** | 0.09 |

| Radical Right Opposition | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.10 | 0.73 *** | 0.10 | 0.71 *** | 0.12 | 0.60 *** | 0.11 |

| Other | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.59 *** | 0.15 | 0.61 *** | 0.17 | 0.44 ** | 0.16 |

| No Vote | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.21 | 0.14 | 0.43 ** | 0.15 | 0.55 ** | 0.18 | 0.34 * | 0.16 |

| Efficacy: Understand | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.10 * | 0.04 |

| Efficacy: Qualified | 0.06 * | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| Political Interest | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 ** | 0.04 | -0.04 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| Left-right position | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 *** | 0.01 | 0.06 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.03 * | 0.02 |

| Household income (log) | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.15 *** | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.15 ** | 0.05 |

| Gender: Female | −0.12 ** | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Age (ref: 18–24) | ||||||||||

| 25-34 | −0.08 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.20 | −0.04 | 0.20 |

| 35-44 | −0.22 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.20 | −0.06 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.22 | −0.03 | 0.21 |

| 45-54 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.02 | 0.22 | −0.14 | 0.20 |

| 55-64 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.19 | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.21 | −0.17 | 0.20 |

| 65+ | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.18 | −0.13 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.21 | −0.20 | 0.20 |

| Education (ref: low) | ||||||||||

| middle | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.08 |

| higher | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.18 * | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.17 * | 0.08 |

| other | −0.34 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.30 | −0.49 | 0.27 | −0.82 * | 0.33 | −0.55 | 0.31 |

| Random Effects | ||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.53 | |||||

| τ00 | 0.20 id | 0.41 id | 0.55 id | 0.77 id | 0.56 id | |||||

| ICC | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.51 | |||||

| N | 833 id | 829 id | 833 id | 830 id | 828 id | |||||

| Observations | 2204 | 2140 | 2204 | 2170 | 2137 | |||||

| Marginal / Cond. R2 | 0.137 / 0.438 | 0.102 / 0.480 | 0.272 / 0.714 | 0.223 / 0.703 | 0.217 / 0.618 | |||||

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

- *** p < 0.001

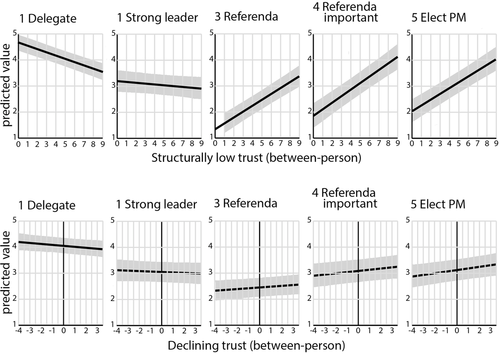

Figure 1 visualizes the predicted values along groups with different levels and dynamics of political trust of all models in Table 4. Structurally low and declining trust beget less support for delegation and boost support for direct decision making. Only the already weak, negative relationship between structurally low trust and support for political authoritarianism loses significance (see Table 4 M2). This suggests that party affiliation and political interest may confound the link between these factors.

The three sets of variables added in Table 4 have independent effects on decision-making preferences. Vote choice in the 2017 general Dutch elections has a particularly strong association with decision-making preferences. Compared to supporters of coalition parties, supporters of opposition parties favour both frequent and selective use of referenda and direct election of the Prime Minister. This holds for supporters of the radical right in particular.12 Supporters of left-wing opposition parties most strongly reject political authoritarianism.13 Respondents who feel qualified to participate in politics express more support for representative decision-making and those who feel they have a good understanding of politics reject the direct election of the Prime Minister. Politically interested respondents reject political authoritarianism more strongly.

Conclusion and discussion

Concerns about low political trust primarily stem from beliefs about its effects on citizens’ preferences and behaviours (Citrin & Stoker, 2018; Dalton, 2004; Marien & Hooghe, 2011; Van der Meer & Zmerli, 2017). Among these, the link between low trust and preferences for various decision-making arrangements looms particularly large (Norris, 1999a). According to some, political distrust might be inducive to the support of authoritarianism (e.g., Crozier et al., 1975; Mounk, 2018), whereas others argue that distrust might lead to democratic reinvigoration (e.g., Dalton, 2004; Norris, 2011). Our paper aims to shed light on these consequences by comparing rivalling theories about the role of trust and by paying closer attention to the individual-level dynamics of trust attitudes.

Existing rivalling theories of Alienated, Critical and Stealth Democratic Citizenship link low political trust to preferences for decision-making arrangements. Yet, implicitly, these theories refer to distinct components, namely structurally low and dynamically declining trust. These implicit components remained largely untested in empirical research. We put rivalling expectations to the test via REWB models of individual panel survey data ranging from 2017 to 2020.

Three themes emerge from the results of these tests. First, as predicted by all three theories, low political trust, whether structural or declining, is associated with a rejection of representative decision making, the status quo in representative democracies. Specifically, the absence of trust prompts less support for delegation of decision making to elected representatives. These results confirm earlier hypotheses and findings (Coffé & Michels, 2014, p. 7; Dalton et al., 2001, p. 148) and suggest that the absence of political trust prompts a rejection of the status quo.

Second, our findings shed some light on the empirical reach of the three rivalling theories. Evidently, it is easier to reject the status quo than to embrace any singular alternative to that status quo. In that light, we find no evidence whatsoever for alienated citizenship theory. Structurally low trust does not beget a process of withdrawal, but a stronger desire of direct involvement in political decisions. Relatedly, structurally low trust does not yield support for political authoritarianism as theories of democratic deconsolidation hypothesize (Mounk, 2018). Evidence for stealth democracy theory and critical citizenship theory is stronger. That structurally low trust is related to support for direct democratic modes of government points in the direction of stealth democracy, even though we do not find higher support for more authoritarian (i.e., less pluralist) modes of government. Possibly, this may be because the authoritarian leadership emphasized in our measure is unaccountable but not necessarily perceived to be ‘objective and largely invisible’ (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002, p. 239). There are limits, it appears, to the types of decision-making arrangements structural distrust begets.

Similarly, we find some but not full support for critical citizenship theory. Critical citizenship posits that declining trust begets an attempt to close the gap between democratic ideals and practice. On the one hand, declining trust motivates individuals to seek more direct control of decision making. On the other hand, as declining trust fails to generate a rejection of authoritarian decision-making arrangements that limit citizen control, the case for distrust as an attitude exclusively spurring critical citizenship is harder to make.

Third, our findings have a more generic implication to political trust research. It shows the use of disentangling between-person differences (structurally low trust) from within-person changes in trust (declining trust). Most studies in the field have tended to conflate changes and levels of trust, and operationalize both as between-person differences in cross-sectional studies. We find that structurally low trust and declining trust have distinct effects on preferences for decision-making arrangements. Yet, although the effects of levels and changes are distinct, the direction of these effects are rather similar.

These findings raise new questions. First, our study suggests that changes in political trust during a single governmental period affects support for decision-making processes. Low and declining political trust tends to stimulate support for direct democratic arrangements such as referenda and directly elected heads of government. This might be one mechanism that links political distrust to support for populist parties, which tend to combine elite-challenging and direct-democratic rhetoric. Populism conceptually binds political distrust to decision-making reforms such as the use of referenda; empirical measures of populism overlap with both elements (cf. Geurkink et al., 2020; Wuttke et al., 2020). Hence, concurrently, the connection between political distrust and support for direct democratic arrangements may be strengthened by populist parties.

Second, we are unable to distinguish short-term declines (in response to a specific government or event) from more monotonic long-term declines (covering multiple governments and events). Distinguishing such monotonic declines in political trust may not only provide more insight about its consequences, but may also hold some clues to the perennial question ‘how much political trust is too little or too much for the collective good?’ (Citrin & Stoker, 2018, p. 64). Yet, that requires individual-level panel designs that tap into even longer time spans, across multiple election cycles and ideally across multiple countries.

More empirical research is needed to assess the dynamics of political trust and their consequences, which have long remained undertheorized. Effects of political trust play out differently at different levels of analysis. We encourage future scholarship to further delineate existing theories by assessing whether their predictions are primarily about low levels of trust or declining levels of trust. The conflation of the two in empirical models on cross-sectional data limits tests of theories on the consequences of political trust as between-person differences and within-person fluctuations in trust are distinct and may yield distinct consequences.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), grant no. 452-16-001.

Acknowledgements

This project benefited from helpful feedback from members of the “Challenges to Democratic Representation” program group at the Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research (AISSR). We are also grateful to Dr. Eefje Steenvoorden who provided valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest